Aristaeus

A-List Customer

- Messages

- 407

- Location

- Pensacola FL

http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/events/wwii-pac/midway/midway.htm

"

Preparations for Battle, March 1942 to 4 June 1942 - Overview

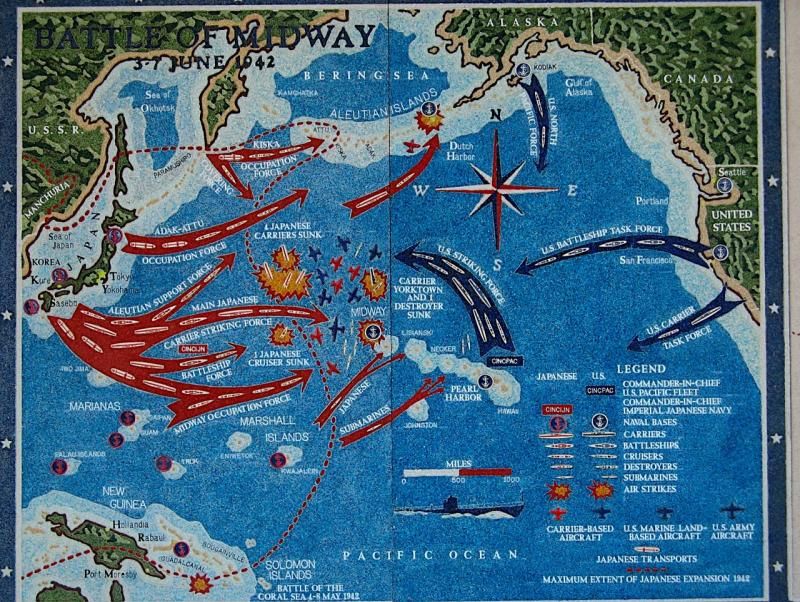

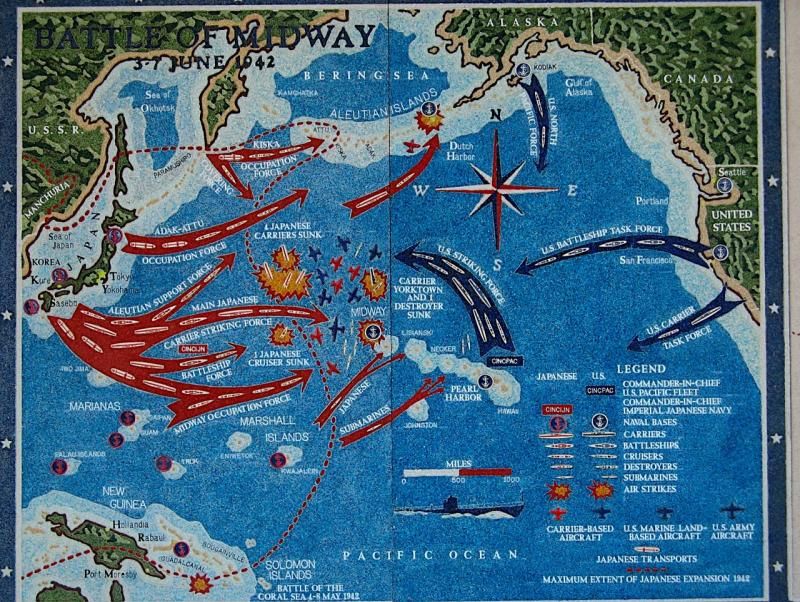

By March 1942, Japanese Navy strategists had achieved their initial war goals much more easily than expected. They had therefore abandoned the prewar plan to then transition to a strategic defensive posture, but there was still dispute on how to maintain the offensive. Moving further south in the Pacific would isolate Australia, and possibly remove that nation as a threat to the freshly-expanded Japanese Empire.

However, the American island base at Midway was also an attractive target, and the Doolittle Raid on Japan prompted a decision to attack there as the next major offensive goal. Midway was a vital "sentry for Hawaii", and a serious assault on it would almost certainly produce a major naval battle, a battle that the Japanese confidently expected to win. That victory would eliminate the U.S. Pacific fleet as an important threat, perhaps leading to the negotiated peace that was Japan's Pacific War "exit strategy.

The Japanese planned a three-pronged attack to capture Midway in early June, plus a simultaneous operation in the North Pacific's Aleutian Islands that might provide a useful strategic diversion. In the van of the assault would be Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's aircraft carrier force, which would approach from the northwest, supress Midway's defenses and provide long-range striking power for dealing with American warships. A few hundred miles behind Nagumo would come a battleship force under Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto that would contain most of the operation's heavy gun power. Coming in from the West and Southwest, forces under Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo would actually capture Midway. Kondo's battleships and cruisers represented additional capabilities for fighting a surface action.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, two things went wrong even before the Midway operation began. Two of Nagumo's six carriers were sent on a mission that resulted in the Battle of Coral Sea. One was badly damaged, and the other suffered heavy casualties to her air group. Neither would be available for Midway.

Even more importantly, thanks to an historic feat of radio communications interception and codebreaking, the United States knew its enemy's plans in detail: his target, his order of battle and his schedule. When the battle opened, the U.S. Pacific fleet would have three carriers waiting, plus a strong air force and reinforced ground defenses at the Midway Base.

Scouting and Early Attacks from Midway, 3-4 June 1942

Forewarned by Pacific Fleet codebreaking, Midway's patrol planes searched out hundreds of miles along probable Japanese approach routes. First contact was made with a pair of minesweepers some 470 miles to the west southwest at about 0900 on 3 June 1942. Within a half-hour, another PBY spotted the enemy's transport group, heading east about 700 miles west of Midway. Later that day, six Army B-17s bombed the transports, the Battle of Midway's first combat action, but only achieved near-misses. The Japanese were undeterred.

During the evening, four PBY-5A amphibians took off to make a night torpedo strike. Encountering the Japanese transport force in the early hours of 4 June, the slow patrol planes hit the oiler Akebono Maru with one torpedo, the only successful U.S. aerial torpedo attack of the entire battle. However, the damaged Japanese ship was able to keep up as the formation continued on.

Soon after 0530 on the morning of 4 June, about 200 miles northwest of Midway, a PBY reported the first contact with the Japanese carrier force, which had already launched over a hundred bombers and fighters to attack the American base. These were seen by another PBY several minutes later. The patrol planes' warnings prompted Midway to get all its aircraft in the air and to bring its defenses to full readiness. They also told the U.S. carrier task forces the enemy's approximate location and course, vital information sent from beyond the normal scouting range of the carriers' own planes. The Battle of Midway now began in earnest.

Japanese Air Attack on Midway, 4 June 1942

At 0430 in the morning of 4 June 1942, while 240 miles northwest of Midway, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's four carriers began launching 108 planes to attack the U.S. base there. Unknown to the Japanese, three U.S. carriers were steaming 215 miles to the east. The two opposing fleets sent out search planes, the Americans to locate an enemy they knew was there and the Japanese as a matter of operational prudence. Seaplanes from Midway were also patrolling along the expected enemy course. One of these spotted, and reported, the Japanese carrier striking force at about 0530.

That seaplane also reported the incoming Japanese planes, and radar confirmed the approaching attack shortly thereafter. Midway launched its own planes. Navy, Marine and Army bombers headed off to attack the Japanese fleet. Midway's Marine Corps Fighting Squadron 221 (VMF-221) intercepted the enemy formation at about 0615. However, the Marines were immediately engaged by an overwhelming force of Japanese "Zero" fighters and were able to shoot down only a few of the enemy bombers, while suffering great losses themselves. This action convincingly demonstrated the inferiority of the Americans' Brewster F2A-3 "Buffalo" fighter, and the marginal capabilities of the somewhat better Grumman F4F "Wildcat", when confronted by the fast and nimble "Zero". Among the Marine losses was VMF-221's commanding officer, Major Floyd B. Parks.

The Japanese planes hit Midway's two inhabited islands at 0630. Twenty minutes of bombing and straffing knocked out some facilities on Eastern Island, but did not disable the airfield there. Sand Island's oil tanks, seaplane hangar and other buildings were set afire or otherwise damaged. As the Japanese flew back toward their carriers the attack commander, Lieutenant Joichi Tomonaga, radioed ahead that another air strike was required to adequately soften up Midway's defenses for invasion.

Burning oil tanks on Sand Island, Midway, following the Japanese air attack delivered on the morning of 4 June 1942.

These tanks were located near what was then the southern shore of Sand Island. This view looks inland from the vicinity of the beach.

Three Laysan Albatross ("Gooney Bird") chicks are visible in the foreground.

Damage on Sand Island, Midway, following the Japanese air attack delivered on the morning of 4 June 1942.

This view, probably photographed from the powerplant roof, looks roughly southwest, along what was then Sand Island's southern shore. Building in the foreground is the laundry, which was badly damaged by a bomb. Oil tanks are burning in the distance.

Note pilings and surf in the left distance.

"

Preparations for Battle, March 1942 to 4 June 1942 - Overview

By March 1942, Japanese Navy strategists had achieved their initial war goals much more easily than expected. They had therefore abandoned the prewar plan to then transition to a strategic defensive posture, but there was still dispute on how to maintain the offensive. Moving further south in the Pacific would isolate Australia, and possibly remove that nation as a threat to the freshly-expanded Japanese Empire.

However, the American island base at Midway was also an attractive target, and the Doolittle Raid on Japan prompted a decision to attack there as the next major offensive goal. Midway was a vital "sentry for Hawaii", and a serious assault on it would almost certainly produce a major naval battle, a battle that the Japanese confidently expected to win. That victory would eliminate the U.S. Pacific fleet as an important threat, perhaps leading to the negotiated peace that was Japan's Pacific War "exit strategy.

The Japanese planned a three-pronged attack to capture Midway in early June, plus a simultaneous operation in the North Pacific's Aleutian Islands that might provide a useful strategic diversion. In the van of the assault would be Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's aircraft carrier force, which would approach from the northwest, supress Midway's defenses and provide long-range striking power for dealing with American warships. A few hundred miles behind Nagumo would come a battleship force under Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto that would contain most of the operation's heavy gun power. Coming in from the West and Southwest, forces under Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo would actually capture Midway. Kondo's battleships and cruisers represented additional capabilities for fighting a surface action.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, two things went wrong even before the Midway operation began. Two of Nagumo's six carriers were sent on a mission that resulted in the Battle of Coral Sea. One was badly damaged, and the other suffered heavy casualties to her air group. Neither would be available for Midway.

Even more importantly, thanks to an historic feat of radio communications interception and codebreaking, the United States knew its enemy's plans in detail: his target, his order of battle and his schedule. When the battle opened, the U.S. Pacific fleet would have three carriers waiting, plus a strong air force and reinforced ground defenses at the Midway Base.

Scouting and Early Attacks from Midway, 3-4 June 1942

Forewarned by Pacific Fleet codebreaking, Midway's patrol planes searched out hundreds of miles along probable Japanese approach routes. First contact was made with a pair of minesweepers some 470 miles to the west southwest at about 0900 on 3 June 1942. Within a half-hour, another PBY spotted the enemy's transport group, heading east about 700 miles west of Midway. Later that day, six Army B-17s bombed the transports, the Battle of Midway's first combat action, but only achieved near-misses. The Japanese were undeterred.

During the evening, four PBY-5A amphibians took off to make a night torpedo strike. Encountering the Japanese transport force in the early hours of 4 June, the slow patrol planes hit the oiler Akebono Maru with one torpedo, the only successful U.S. aerial torpedo attack of the entire battle. However, the damaged Japanese ship was able to keep up as the formation continued on.

Soon after 0530 on the morning of 4 June, about 200 miles northwest of Midway, a PBY reported the first contact with the Japanese carrier force, which had already launched over a hundred bombers and fighters to attack the American base. These were seen by another PBY several minutes later. The patrol planes' warnings prompted Midway to get all its aircraft in the air and to bring its defenses to full readiness. They also told the U.S. carrier task forces the enemy's approximate location and course, vital information sent from beyond the normal scouting range of the carriers' own planes. The Battle of Midway now began in earnest.

Japanese Air Attack on Midway, 4 June 1942

At 0430 in the morning of 4 June 1942, while 240 miles northwest of Midway, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's four carriers began launching 108 planes to attack the U.S. base there. Unknown to the Japanese, three U.S. carriers were steaming 215 miles to the east. The two opposing fleets sent out search planes, the Americans to locate an enemy they knew was there and the Japanese as a matter of operational prudence. Seaplanes from Midway were also patrolling along the expected enemy course. One of these spotted, and reported, the Japanese carrier striking force at about 0530.

That seaplane also reported the incoming Japanese planes, and radar confirmed the approaching attack shortly thereafter. Midway launched its own planes. Navy, Marine and Army bombers headed off to attack the Japanese fleet. Midway's Marine Corps Fighting Squadron 221 (VMF-221) intercepted the enemy formation at about 0615. However, the Marines were immediately engaged by an overwhelming force of Japanese "Zero" fighters and were able to shoot down only a few of the enemy bombers, while suffering great losses themselves. This action convincingly demonstrated the inferiority of the Americans' Brewster F2A-3 "Buffalo" fighter, and the marginal capabilities of the somewhat better Grumman F4F "Wildcat", when confronted by the fast and nimble "Zero". Among the Marine losses was VMF-221's commanding officer, Major Floyd B. Parks.

The Japanese planes hit Midway's two inhabited islands at 0630. Twenty minutes of bombing and straffing knocked out some facilities on Eastern Island, but did not disable the airfield there. Sand Island's oil tanks, seaplane hangar and other buildings were set afire or otherwise damaged. As the Japanese flew back toward their carriers the attack commander, Lieutenant Joichi Tomonaga, radioed ahead that another air strike was required to adequately soften up Midway's defenses for invasion.

Burning oil tanks on Sand Island, Midway, following the Japanese air attack delivered on the morning of 4 June 1942.

These tanks were located near what was then the southern shore of Sand Island. This view looks inland from the vicinity of the beach.

Three Laysan Albatross ("Gooney Bird") chicks are visible in the foreground.

Damage on Sand Island, Midway, following the Japanese air attack delivered on the morning of 4 June 1942.

This view, probably photographed from the powerplant roof, looks roughly southwest, along what was then Sand Island's southern shore. Building in the foreground is the laundry, which was badly damaged by a bomb. Oil tanks are burning in the distance.

Note pilings and surf in the left distance.