MikeKardec

One Too Many

- Messages

- 1,157

- Location

- Los Angeles

Since there are a good many writers here I thought I'd explore some ideas I've been experimenting with both in my own work and considering in examples of in the work of others. Today I'm going to deal with structure:

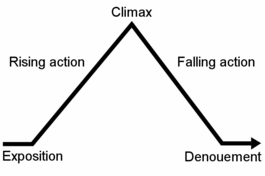

Structure is the geometrical "proof" of your story. It is the all important promise that your story will eventually mean something greater than the sum of its parts, rather than simply being a rambling narrative of disconnected or superficially connected events. The build of a story through its structure toward a meaningful end point is part of your contract with the audience: They let you break into their life with your story, you promise that it will be worth the interruption.

Before the current "religion of structure" completely took over Film and Theater and then slopped out into the world of prose writing, ace screenwriter William Goldman dispensed advice along the lines of "find A structure."

That's a good way of putting it. We do create structure naturally, it’s amazing to see some of the most complex models show up in work where you never gave it the slightest thought. It is a pattern inherent to humanity. But the dogma created by Syd Field and all the supposed screenwriting gurus that followed him is just too narrow if you take it too seriously. It's all useful, incredibly useful, but it’s really just a place to start; a point of departure as you train yourself to create your own interpretation of the structural mechanisms to fulfill that contract with the audience mentioned above. The primary lesson is: audiences get bored so change it up. The secondary lesson is: they need to feel they are getting somewhere meaningful.

There is something about traditional story structure that is built into our psyche. Aristotle kicked things off but people Field, Christopher Vogler, and Blake Snyder, have codified things based upon analyzing success in the motion picture business to a remarkable degree. Some offer three, four, five, or even twelve acts … but it doesn’t matter. Their suggestions are incredibly valuable if taken creatively, but strict adherence has reduced story telling in film to a sort of cartoon kabuki theater. All of them built on the astute psychological observations of Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and Christopher Booker. However, unlike those esteemed gentlemen, the movie gurus have rarely looked deeply into the unconscious and deeply important why of it all. To break the rules constructively you have to understand the purpose, not simply copy the moves of other practitioners.

I’m not going to go into that further than the very basic rules I have laid out but is likely the best single book, if you want to inspire yourself to deep thoughts, is Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots. This is not a book on how to write. It is about the evolving history and purpose of fiction. It is not the be all and end all (it draws heavily on Campbell and Jung) and there are plenty of things about writers and writing that Booker does not understand (or simply forgets to say straight out) but, if you allow yourself to be inspired by it as opposed to taking everything he says for granted, it will make you think about what you are up to with the perspective of someone who has devoted a great deal of time to literary scholarship. It’s a big book but it’s less time consuming than a Masters in English!

Back to the subject …

Three Act Structure is obsessed upon merely because it is the fewest number of acts you can have. Good writing is all about manipulating and reversing Expectation (the expectations of the audience or characters) versus Outcome. The Hope that things will go well but the Fear that they might not. Though always useful, at certain critical junctures this can deliver that “no going back” moment that is often talked about. It is the geometrical "proof" that your story has reached a minor conclusion which will be the foundation for future developments. In my opinion, this defines an Act. It is a preponderance of evidence that is best communicated in such a way that it is a surprise; a reversal of outcome that defies someone's (again, audience or character's) expectations yet is still logical. This is common in fiction and film yet is it also a part of good journalism.

So, okay, if three act structure is the minimum, what does that mean? The First Act introduces. The Last Act resolves. Everything in between elaborates. Hopefully, it also heightens. But, believe me, though professionals tend to discuss structure as if it was limited to three acts, that is just for convenience. In fact I'd argue that Three Acts is a complete misnomer. If Shakespeare didn't dispel this idea then Series TV should have.

I'd also argue that the most important structural aspect of story telling, because it goes to the heart of what your story is about as opposed to simply how it's being told, is the Mid Point. Now that term was probably coined by Syd Field and, as a simple signpost, it is extremely simplistic and stripped of meaning. To get more to the point I call this moment The Dilemma or The Fulcrum. It is generally the moment where the underlying issues in the story get serious, where the theme becomes clear. For people here at this site, think of the scene in Casablanca when Ilsa confronts Rick after closing time and you realize that the real story is about how these people will deal with who they have become since Paris. This Dilemma is possibly the deepest question about not being able to go back. It may not be as obvious and sudden as the more plot oriented and mechanical First Act and Last Act transitions but it can be the most critical of all the points in a story … so critical in fact that Shakespeare often gave it an "act" of it's own; the Third Act of his Five Act Structure. Skip to the middle of any film you are familiar with and you will see what I’m talking about. It is also present in prose but the exact moment (page) can be a bit harder to identify precisely.

The Mid Point really turns most Three Act Structures into Four Act Structures ... but my concept is "who cares." The reality is that you have a First Act, a Last Act, and everything in between. I used to write TV movies. Because of commercial breaks we were required to produce 7 to 8 acts in 94 to 89 pages. Following William Goldman's advice, we are talking about finding A structure, not dogmatically following an externally imposed template (in TV this means a not template that comes from feature films). Releasing yourself from the dictatorship of the structural monolith also helps you deal with issues like non chronological story telling and whether structure is related to the order in which the events happened in fictional story time (as in a story with flashbacks) or in the viewing or reading order in which the audience perceives them. I'm still struggling with that myself, some of it is reading order but ...

Practically I find the best way of working is like this: As you start to get an idea of what your story is figure out a potential Dilemma or Fulcrum early on. Following the traditional advice for First and Last Act transitions get those roughly figured out. Typically they are: the moment the conflict becomes apparent, and the moment when resolving it becomes unavoidable. Then just write like a maniac and get something down on paper, a version of the whole story that pays as little attention to structure as possible, just enough to get you to the end. With this in the bag go back and, as part of the rewriting process, apply all the other structural concepts that you have learned where ever you have learned them and see if they fit or help your story. Take them SERIOUSLY but not as rules, just suggestions. Use them to rediscover and redefine what your story is and is about. Don't be afraid to move some of the lesser elements around a bit. The positioning needs to be right for your story. As long as you have thought long and hard about why you are breaking the rules there is no need to follow a generic template.

I have a 20 page outline of every theory of story structure I have ever run across all superimposed on one and other like one of those sets of transparencies in an anatomy text book. If I tried to write a first draft using it I would lose my mind. It is the ultimate tool if I want to destroy my initial burst of creativity. BUT, it is a great tool when it comes to discovering, in revision, if I started to let things drag, if I didn't change it up soon enough, and if I didn't change it up to the right sort of thing given where I am in the story.

Having a good background in story structure is very important. We understand and control the world through telling stories and structure is the underlying code to those stories. However, in recent years a superficial understanding of structure has led to the imposition of superficial theories of structure. As a writer it is something that you’d better learn, because if you don’t you will be limited by how much of it you understand naturally or unconsciously. At the same time you don’t want to be limiting yourself with a bunch of silly and much worse, misunderstood, rules!

Structure is the geometrical "proof" of your story. It is the all important promise that your story will eventually mean something greater than the sum of its parts, rather than simply being a rambling narrative of disconnected or superficially connected events. The build of a story through its structure toward a meaningful end point is part of your contract with the audience: They let you break into their life with your story, you promise that it will be worth the interruption.

Before the current "religion of structure" completely took over Film and Theater and then slopped out into the world of prose writing, ace screenwriter William Goldman dispensed advice along the lines of "find A structure."

That's a good way of putting it. We do create structure naturally, it’s amazing to see some of the most complex models show up in work where you never gave it the slightest thought. It is a pattern inherent to humanity. But the dogma created by Syd Field and all the supposed screenwriting gurus that followed him is just too narrow if you take it too seriously. It's all useful, incredibly useful, but it’s really just a place to start; a point of departure as you train yourself to create your own interpretation of the structural mechanisms to fulfill that contract with the audience mentioned above. The primary lesson is: audiences get bored so change it up. The secondary lesson is: they need to feel they are getting somewhere meaningful.

There is something about traditional story structure that is built into our psyche. Aristotle kicked things off but people Field, Christopher Vogler, and Blake Snyder, have codified things based upon analyzing success in the motion picture business to a remarkable degree. Some offer three, four, five, or even twelve acts … but it doesn’t matter. Their suggestions are incredibly valuable if taken creatively, but strict adherence has reduced story telling in film to a sort of cartoon kabuki theater. All of them built on the astute psychological observations of Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and Christopher Booker. However, unlike those esteemed gentlemen, the movie gurus have rarely looked deeply into the unconscious and deeply important why of it all. To break the rules constructively you have to understand the purpose, not simply copy the moves of other practitioners.

I’m not going to go into that further than the very basic rules I have laid out but is likely the best single book, if you want to inspire yourself to deep thoughts, is Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots. This is not a book on how to write. It is about the evolving history and purpose of fiction. It is not the be all and end all (it draws heavily on Campbell and Jung) and there are plenty of things about writers and writing that Booker does not understand (or simply forgets to say straight out) but, if you allow yourself to be inspired by it as opposed to taking everything he says for granted, it will make you think about what you are up to with the perspective of someone who has devoted a great deal of time to literary scholarship. It’s a big book but it’s less time consuming than a Masters in English!

Back to the subject …

Three Act Structure is obsessed upon merely because it is the fewest number of acts you can have. Good writing is all about manipulating and reversing Expectation (the expectations of the audience or characters) versus Outcome. The Hope that things will go well but the Fear that they might not. Though always useful, at certain critical junctures this can deliver that “no going back” moment that is often talked about. It is the geometrical "proof" that your story has reached a minor conclusion which will be the foundation for future developments. In my opinion, this defines an Act. It is a preponderance of evidence that is best communicated in such a way that it is a surprise; a reversal of outcome that defies someone's (again, audience or character's) expectations yet is still logical. This is common in fiction and film yet is it also a part of good journalism.

So, okay, if three act structure is the minimum, what does that mean? The First Act introduces. The Last Act resolves. Everything in between elaborates. Hopefully, it also heightens. But, believe me, though professionals tend to discuss structure as if it was limited to three acts, that is just for convenience. In fact I'd argue that Three Acts is a complete misnomer. If Shakespeare didn't dispel this idea then Series TV should have.

I'd also argue that the most important structural aspect of story telling, because it goes to the heart of what your story is about as opposed to simply how it's being told, is the Mid Point. Now that term was probably coined by Syd Field and, as a simple signpost, it is extremely simplistic and stripped of meaning. To get more to the point I call this moment The Dilemma or The Fulcrum. It is generally the moment where the underlying issues in the story get serious, where the theme becomes clear. For people here at this site, think of the scene in Casablanca when Ilsa confronts Rick after closing time and you realize that the real story is about how these people will deal with who they have become since Paris. This Dilemma is possibly the deepest question about not being able to go back. It may not be as obvious and sudden as the more plot oriented and mechanical First Act and Last Act transitions but it can be the most critical of all the points in a story … so critical in fact that Shakespeare often gave it an "act" of it's own; the Third Act of his Five Act Structure. Skip to the middle of any film you are familiar with and you will see what I’m talking about. It is also present in prose but the exact moment (page) can be a bit harder to identify precisely.

The Mid Point really turns most Three Act Structures into Four Act Structures ... but my concept is "who cares." The reality is that you have a First Act, a Last Act, and everything in between. I used to write TV movies. Because of commercial breaks we were required to produce 7 to 8 acts in 94 to 89 pages. Following William Goldman's advice, we are talking about finding A structure, not dogmatically following an externally imposed template (in TV this means a not template that comes from feature films). Releasing yourself from the dictatorship of the structural monolith also helps you deal with issues like non chronological story telling and whether structure is related to the order in which the events happened in fictional story time (as in a story with flashbacks) or in the viewing or reading order in which the audience perceives them. I'm still struggling with that myself, some of it is reading order but ...

Practically I find the best way of working is like this: As you start to get an idea of what your story is figure out a potential Dilemma or Fulcrum early on. Following the traditional advice for First and Last Act transitions get those roughly figured out. Typically they are: the moment the conflict becomes apparent, and the moment when resolving it becomes unavoidable. Then just write like a maniac and get something down on paper, a version of the whole story that pays as little attention to structure as possible, just enough to get you to the end. With this in the bag go back and, as part of the rewriting process, apply all the other structural concepts that you have learned where ever you have learned them and see if they fit or help your story. Take them SERIOUSLY but not as rules, just suggestions. Use them to rediscover and redefine what your story is and is about. Don't be afraid to move some of the lesser elements around a bit. The positioning needs to be right for your story. As long as you have thought long and hard about why you are breaking the rules there is no need to follow a generic template.

I have a 20 page outline of every theory of story structure I have ever run across all superimposed on one and other like one of those sets of transparencies in an anatomy text book. If I tried to write a first draft using it I would lose my mind. It is the ultimate tool if I want to destroy my initial burst of creativity. BUT, it is a great tool when it comes to discovering, in revision, if I started to let things drag, if I didn't change it up soon enough, and if I didn't change it up to the right sort of thing given where I am in the story.

Having a good background in story structure is very important. We understand and control the world through telling stories and structure is the underlying code to those stories. However, in recent years a superficial understanding of structure has led to the imposition of superficial theories of structure. As a writer it is something that you’d better learn, because if you don’t you will be limited by how much of it you understand naturally or unconsciously. At the same time you don’t want to be limiting yourself with a bunch of silly and much worse, misunderstood, rules!

Last edited: